God himself cares for orphans and expects his people to do so as well. This much is not particularly controversial. It’s barely debatable.

But as we move past the theological and abstract into the practical and concrete, things quickly get much more complex. How we should care for the world’s 150,000,000 orphans?

We all recoil in disgust at the notion that any child should ever be sentenced to languish—untaught and unloved—in a squalid, Dickensian, prison-like institution. This healthy aversion to the warehousing of orphaned children has led many governments and charitable organizations to emphasize family preservation and kinship adoption as alternatives to orphanages—considering these the “best-case scenario” solutions.

It has also driven many of us who do provide permanent residential orphan care to develop healthier models of service. Asia’s Hope, the organization I work for, has spent the last 14 years investing in family-style residential care, where orphaned and abandoned children are placed with full-time moms and dads, uncles and aunts, brothers and sisters. They are afforded the best possible education, counseling and life skills training available. Many of our graduates are successful university students, entrepreneurs, and professionals; their success outpaces even that of many of their non-orphaned peers.

Unfortunately, in an attempt to avoid the tragic mistakes of the past, an increasing number of orphan advocates now consider the permanent placement of a child into any kind of residential care setting an out-dated, inhumane, and ultimately harmful option. Some have even called for a moratorium on the establishment of all new orphanages and the closure of existing ones. The proposed Children in Families First Act, for example, will pressure foreign nations to limit the growth of or even eliminate orphanages and group homes as a condition of U.S. aid.

This kind of overcorrection is misguided and dangerous, and risks throwing out literal babies with the proverbial bathwater.

There is no credible scenario under which the proposed alternatives can be implemented for the vast majority of our world’s 150,000,000 orphans. According to some estimates, a child is orphaned every second of every single day, often as a result of abuse, neglect, extreme poverty or mental illness. We are already way behind in providing even the most basic resources for these children; we can hardly afford to discard, disparage or defund improved, improving and improvable care models that are working today.

The practical obstacles to global implementation of alternative care models aside, there will always be some cases in which residential orphan care will provide the best solution for an orphaned child.

Due to general scarcity of resources and lack of social service structures in many impoverished countries, the vast majority of orphaned children alive today will never benefit from the kinds of care advocated by orphanages’ most vocal opponents. As Christians who care about orphans, we certainly need to fund and advocate for organizations working to keep children in their families and communities of origins. But we also need to recognize that there will always be some cases in which residential orphan care will provide the best solution for an orphaned child.

In my experience, there are children for whom a placement with an aunt, uncle or grandparent — or adoption by a member of the community — would provide an experience inferior to placement in a well-funded, properly organized orphanage:

1) When a foster, adoptive or kinship care placement would separate siblings that could be kept together in a residential program.

So often kinship care or adoption splits up a primary family relationship (brother to sister, for instance) to maintain a secondary or tertiary (uncle to nephew, grandmother to granddaughter). By placing an entire sibling group—intact—into a children’s home, we are actively preserving the most important remaining bonds an orphan child needs to be successful in life.

2) When the child’s status as an orphan would relegate them to an inferior or subservient role within the home

Children placed with extended family often fall prey to the “Cinderella Syndrome,” where they are permanently relegated to an underclass within the family. The family’s birth children go to school and receive a larger portion of the family’s emotional and material support, while the orphaned children are resented and or treated as domestic servants. In an excellent residential care setting, each child can be guaranteed equal treatment, regardless of their social status or the circumstances that led them to orphanhood.

3) When foster-care or kinship placement is likely to be temporary

Stability and permanence plays a greater role in predicting long-term success for a child than familial proximity or even family size. We see this clearly in American children’s services structures, where kids are bounced back and forth between unsafe and unstable birth families and temporary foster families. On the other hand, when an organization like Asia’s Hope admits a child or a sibling group, we can guarantee permanent, uninterrupted care for the remainder of their childhood.

4) When legal or social factors make adoption or kinship care placement illegal, unsafe or infeasible

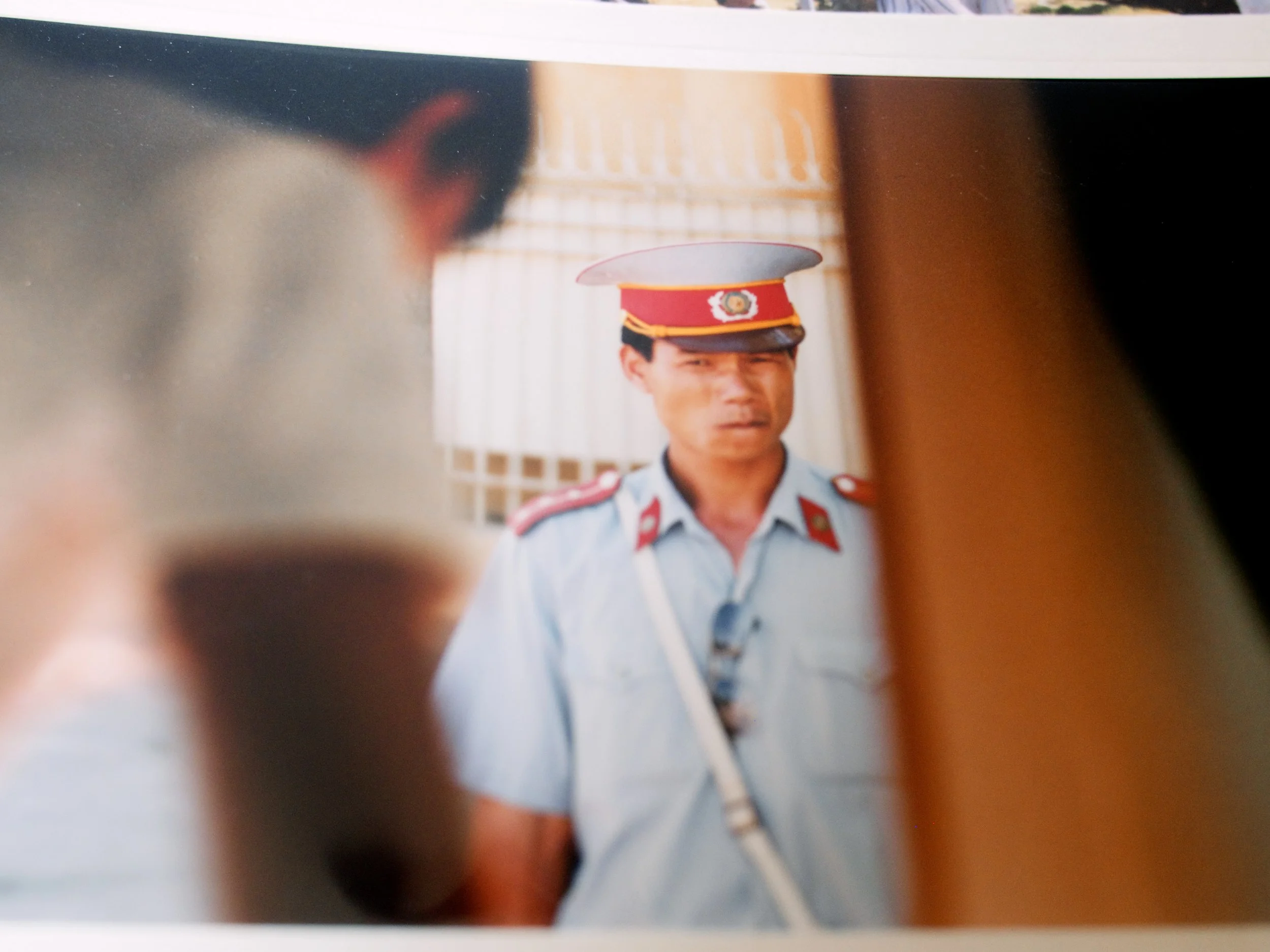

In China, the “one-child policy” renders the legal adoption of hundreds of thousands of “extra” children by extended family members unthinkable. To report a birth that violates the strictly-enforced law would put the entire family—and the birth mother most directly—in grave danger of fines, penalties, even prison. In other parts of the world, orphaned children are believed to be cursed, the object of a powerful spirit’s wrath, and are neither worthy of nor entitled to dignity and protection.

A significant, long-term investment is needed in these types of societies, and requires not just NGO generosity, but the commitment of local governments to support, foster and oversee competent social service mechanisms. It also requires the dismantling of deeply entrenched systems of power that lead to injustice and oppression of the poor. As Jesus said, “The poor will always be with you.” Until the Kingdom comes in its fullness, we will always struggle against powerful forces that orphan and exploit children.

We need to reject both overcorrection and utopianism, recognizing that systems of injustice are inter-connected and multi-faceted. There can never be a “silver bullet” or a single solution to the world’s orphan crisis. We should support organizations and individuals doing good work across the entire spectrum of care, advocating for excellence in both new and existing models. We must commit to working together, valuing unity rather than uniformity.